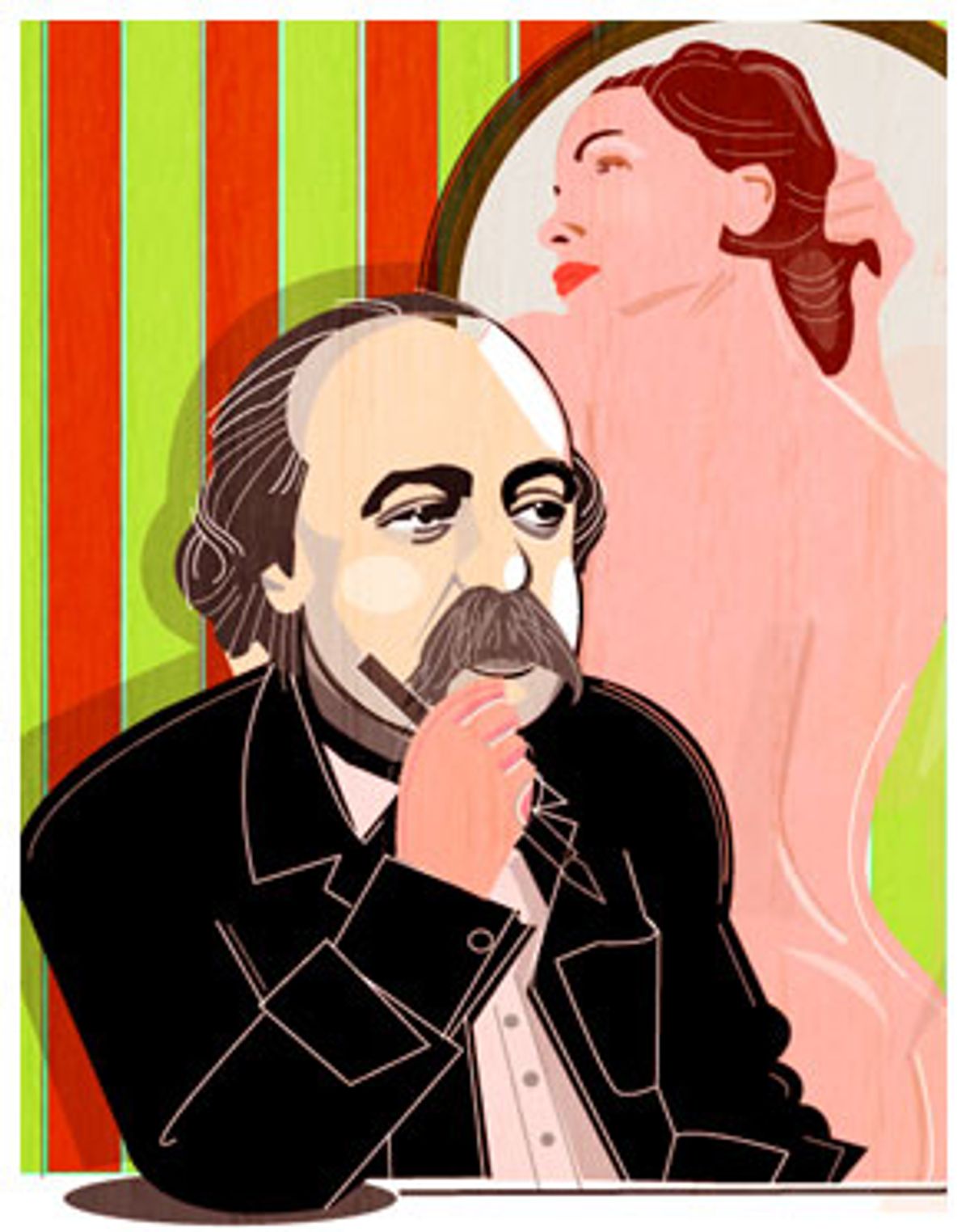

I've always loved Gustave Flaubert. Not his work, exactly, since until recently I hadn't actually read any of it, but the idea of him. Here was a writer who had been satisfied to produce two polished pages a week, who believed in nothing so much as the power of precisely rendered prose. Here was a writer who, according to legend, had been so drawn to his character, Emma Bovary, he'd masturbated about her at his desk. Here was a writer whose adage, "Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work," offered a justification for my slow slippage from bohemia to the middle class.

I was 24 when I heard that statement, and not long afterward I bought a used Signet Classics edition of "Madame Bovary," which I've carried around for 20 years. The way I saw it, Flaubert's novel represented a promise, an opportunity, a work I knew I'd read -- just give me time. Yet when I finally got around to it this summer, I couldn't help wondering if it would measure up. Two decades, after all, is a long time to anticipate anything, especially a work that Frank O'Connor called "possibly the most beautifully written book ever composed; undoubtedly the most beautifully written novel." In Flaubert's words: "One must not touch idols; the gilt rubs off on one's hands."

So, does "Madame Bovary" live up to expectations? To be honest, it depends on what those expectations are. Originally published in 1857, it is, in a very real sense, the first modern novel, which has at its center the emptiness of bourgeois life. A century and a half later, that's a common, even hackneyed, theme, but in its time, much of what Flaubert recorded must have been revolutionary indeed. Unfolding in Yonville-l'Abbaye, a small farming town in 19th century France, the book evokes the petty ambitions and vapid homilies that yoke not only Emma, but every character. There is Homais, the village pharmacist, a blowhard who convinces Emma's husband, Charles, the local physician, to operate on a porter with a clubfoot; gangrene sets in, and the porter loses a leg. Or Lheureux, a wealthy merchant who duns Emma into unnecessary extravagances while financing and refinancing the loans that will bring her to ruin. Rodolphe, Emma's first lover, seduces her even as he plans his escape: "Three flattering words and she'd adore me, I'm sure," he thinks at their first meeting. "How tender and charming it would be. But how would I get rid of her later?" Then there is the curi, with his grease-stained cassock, who mistakes creature comforts for spiritual and falls asleep while watching over Emma's lifeless body at novel's end.

In such a setting, Emma is less a fallen woman than an extreme expression of a culture with no values, without the will to control itself. Even the pious are compromised, a point Flaubert gets across using Emma's mother-in-law. "You know what your wife needs? To be forced to work," she tells her son, and when he protests that she keeps busy, his mother refutes the claim. "Keeps busy!" she declares. "Doing what? Reading novels, evil books, books against religion where they make fun of priests by quoting Voltaire. But that goes far, my poor child, and a person without religion will always end up bad."

What's most intriguing about "Madame Bovary" is its pacing, its relationship with time. On some level, this is the novel's true subject, with Emma a prototypic woman of leisure, as her mother-in-law suggests. For such a contemporary concept, however, Flaubert develops it unhurriedly, in almost classical terms. To call the novel deliberate is an understatement, but this is not a criticism. Rather, Flaubert is mirroring the society in which he lived, one so unlike ours as to be completely alien. It's not that the writing is slow, but that reality is, that time doesn't function quite the same. Throughout the novel, days stretch and bend as if elastic; we can feel it in the pull of Emma's boredom, the fine line between ennui and desire. "Deep down within her," Flaubert writes, "she was waiting for something to happen ... Other people's existences, as dull as they were, at least had the chance of something happening. Some occurrence would occasionally bring about a series of ups and downs or a change of scene. But it was God's will that nothing should happen to her. The future was a totally dark corridor with a solidly locked door at its end."

Even the structure of the book reflects this; when Emma and Charles move to Yonville-l'Abbaye, Flaubert spends four pages describing the village, then four more introducing the townsfolk, before the Bovaries appear. That's fascinating from both a literary and a sociological standpoint, since not only would a current writer never do this, it's just not how we see the world. In a culture like ours, marked by information overload, by jump-cuts, sampling, multitasking, our brains are no longer wired in such a way. To read "Madame Bovary," then, is not just to be exposed to a different aesthetic, but to an entirely different way of seeing, one that has, for all intents and purposes, literally disappeared.

Of course, were "Madame Bovary" merely a historical oddity, there would be no reason to read it anymore. Yet Flaubert's truest achievement is how, despite being a writer of his moment, he transcends that moment by getting at some basic human truths. Of these, perhaps the most essential is the hypocrisy of moral standards, which, then as now, seem manufactured to support the status quo. "Ah, but there are two moralities," Rodolphe tells Emma, as they listen to self-congratulatory speeches at an agricultural show. "The petty, conventional morality, the morality of men, which is constantly changing and which makes such a loud noise, floundering about on the earth like this collection of imbeciles you see before you. But the other, the eternal morality, is all around and above us like the countryside that surrounds us and the blue sky that sends down its light." Such remarks, to be sure, are a ploy -- an attempt to subvert Emma's middle-class defenses, to talk her into adultery. Yet, irony aside, it's impossible not to notice Flaubert manipulating the dialogue to frame a larger commentary.

The same is true of Emma's dissatisfaction, which she cannot come to terms with, even as it leads to her own degradation and death. "Why then," Flaubert writes, "was life so inadequate? Why did she feel this instantaneous decay of the things she relied on? If there existed somewhere a strong and handsome being, a valiant nature imbued with both exaltation and refinement, the heart of a poet in the shape of an angel, a lyre with strings of bronze, sounding elegiac nuptial songs towards the heavens -- why, why could she not find him? How impossible it seemed! And anyway, nothing was worth looking for; everything was a lie. Each smile hid a yawn of boredom, each joy a curse, each pleasure its aftermath of disgust, and the best of kisses left on your lips only the unattainable desire for a higher delight."

It is here that Flaubert highlights the complexity that drives this novel: the ambiguity of desire. Yes, Emma is shallow, amoral, a woman who debases herself increasingly as the book goes on. The same, though, could be said of everyone else, from the matrons who wag their tongues at her behavior to the men who take advantage of her, whether in business or in bed. Ultimately, Flaubert is saying, no one is innocent, except perhaps for Charles, who is too blind or placid to see what's before his eyes. Still, if such a bleak perspective appears somehow modern, I prefer to regard it as simply human, an expression of who we are. Corruption, after all, has been with us since the beginning; it may be the most enduring characteristic we have. Or as Flaubert puts it, "Doesn't this conspiracy of society revolt you? Is there one ounce of feeling that it does not condemn?"

Shares